Hello everyone,

Recently I sat down to watch The Imitation Game with my daughter, who has been going through a bit of a Benedict Cumberbatch phase lately.

The film is based on the biography Alan Turing: The Enigma.

Like most of you perhaps, I know Alan Turing as the inventor of the computer, as well as the world’s first programmer. The story behind the man is a fascinating one, as is how he conceived of the computer through his idea about mechanising thought.

Who was Alan Turing?

Alan Turing became very famous as a young mathematician for realising that there were some numbers that were uncomputable, meaning literally, if you tried to mechanise thought. So in that sense he literally invented the computer, which at the time was a word for people who calculated things, but we now understand as a machine that’s able to do lots of flexible stuff.

These computers used to be called Universal Turing Machines, after Turing, but Turing’s idea was to imagine mechanising thought and figuring out a way in which theorems and proofs work, and in that process, he proved that there were numbers that could never be computed in a form shorter than the number itself.

Let’s take the number 0.123579… for example. It goes on and on for infinity. The code to generate that number is exactly as long as the number. Well, actually shorter, which is not true of the numbers two, three and four, which we can write a very short code for. But take the square root of two. The square root of two is actually an irrational number, but it is computable in a very short code.

So, the difference between the square root of two and these other numbers was that there was no code that could be written – no mechanised system that could be devised – that would yield the number any more quickly than just randomly tossing the die of what the next digit should be after the decimal point.

Okay, so that sounds very abstract, but what it means is that there are facts about numbers – simple numbers – numbers between zero and one, about which we will never know anything. Not only that, but there’s an infinite number of such numbers, and it’s the largest infinity of the numbers between zero and one. Well, most numbers actually.

Most numbers are numbers about which we will never know anything. This was a cutting edge revelation in a time when people were trying to recover from the wars and they’re trying to find solace and rationality. This belief that everything can be rational and noble was a real kick in the teeth at the time.

Kurt Gödel

Kurt Gödel is another fascinating character, who predates Turing, and gets it all started. So David Hilbert, the most powerful mathematician of the era at the turn of the century, calls for a proof that all true facts among the numbers can be proven to be true. He doesn’t literally mean he wants a list of an infinite number of proofs, he just wants a proof that it can be done. And everyone expects that this is true. So Gödel is the one who deals the first blow before Turing. Turing is really influenced by Gödel’s work, and Gödel shows that there are facts among the numbers that can never be proven to be true. Either the formal system is inconsistent, or there are true facts that can’t be proven, and Gödel rejected inconsistency. So either there’s a bold-faced paradox in mathematics, which he rejected, or there are facts that can’t be proven to be true, which is an opinion shared largely by other people. It would be much worse if one plus one was sometimes two and sometimes three.

Like Turing, Gödel was also a strange character. He was very isolated and very withdrawn and had strange ideas about the afterlife and Platonism. He really believed that mathematics was real in a physical sense. We could never draw a perfect circle, because there’s no such thing as a perfect circle in reality. But he believed that the mental experiment of a perfect circle is sufficient to prove it exists, which is quite insightful and interesting.

What Gödel did was construct a sentence, which basically says this true statement can never be proven. And then he translated it through a very clever cipher into a purely arithmetic statement that was just about numbers, and proved that that equation was correct, and therefore unprovable. Which is true. If it were provable it would have to be incorrect, because the statement said it’s unprovable.

It is possible that you could try to construct such a sentence, but you could not mathematise it, and you wouldn’t prove anything. But Gödel mathematised it perfectly. And ever since then, every mathematician who’s been trying to prove things and getting stuck is always wondering, “Is this one of the things that is not provable?” That is ultimately Gödel’s lesson; that you know it’s true because you step outside of the mathematical system and you reflect on it and you can declare it’s true.

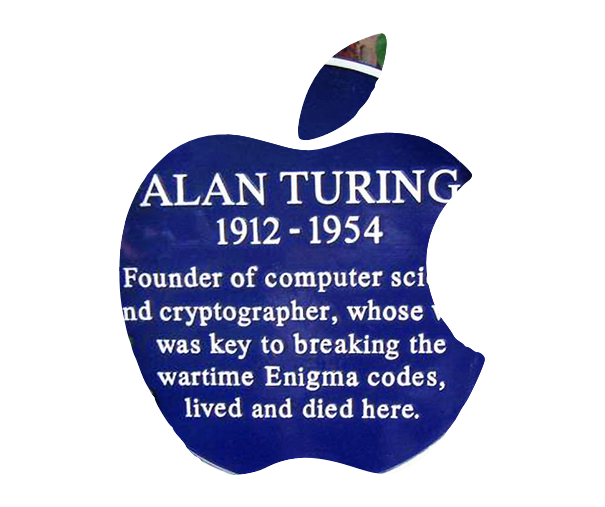

Turing’s link to the Apple logo

Turing was convicted of homosexuality in 1952 and given hormone treatments, which left him depressed and devastated and suicidal, and is largely believed to have taken his own life. He was obsessed with Snow White, which had recently been aired and screened.

Apparently he bit from a poison apple, one that he dipped in cyanide. Interestingly, I have seen it mentioned on multiple web sites that the Apple Mac symbol of the half-eaten apple (the famous apple logo with the bite out of it) is a reference to Turing, because Turing invented the computer in this indirect way, by starting this idea about mechanising thought.

Conclusion

Alan Turing was a strange, but brilliant character. He was very likely autistic, openly gay (and persecuted for his homosexuality), and also contributed significantly to the war effort, turning the tide in favour of the allies by breaking codes.

In many respects he could also be considered the father of AI (artificial intelligence). He not only says, “I bet I could build a machine that could think as well as we do” (meaning that machines could think), but he also says “We are machines that think.”, which really makes him the father of AI. So then he becomes this sort of atheist that gives up all of this other stuff and says, “We simply are machines.”